RESTORATION

We approach restoration from two primary angles that are equally important. Firstly, we attempt to revive the Stories of Jewish Bardejov. Secondly, we work to repair and restore spaces of cultural and religious significance to the Jewish community who once lived in Bardejov.

STORIES

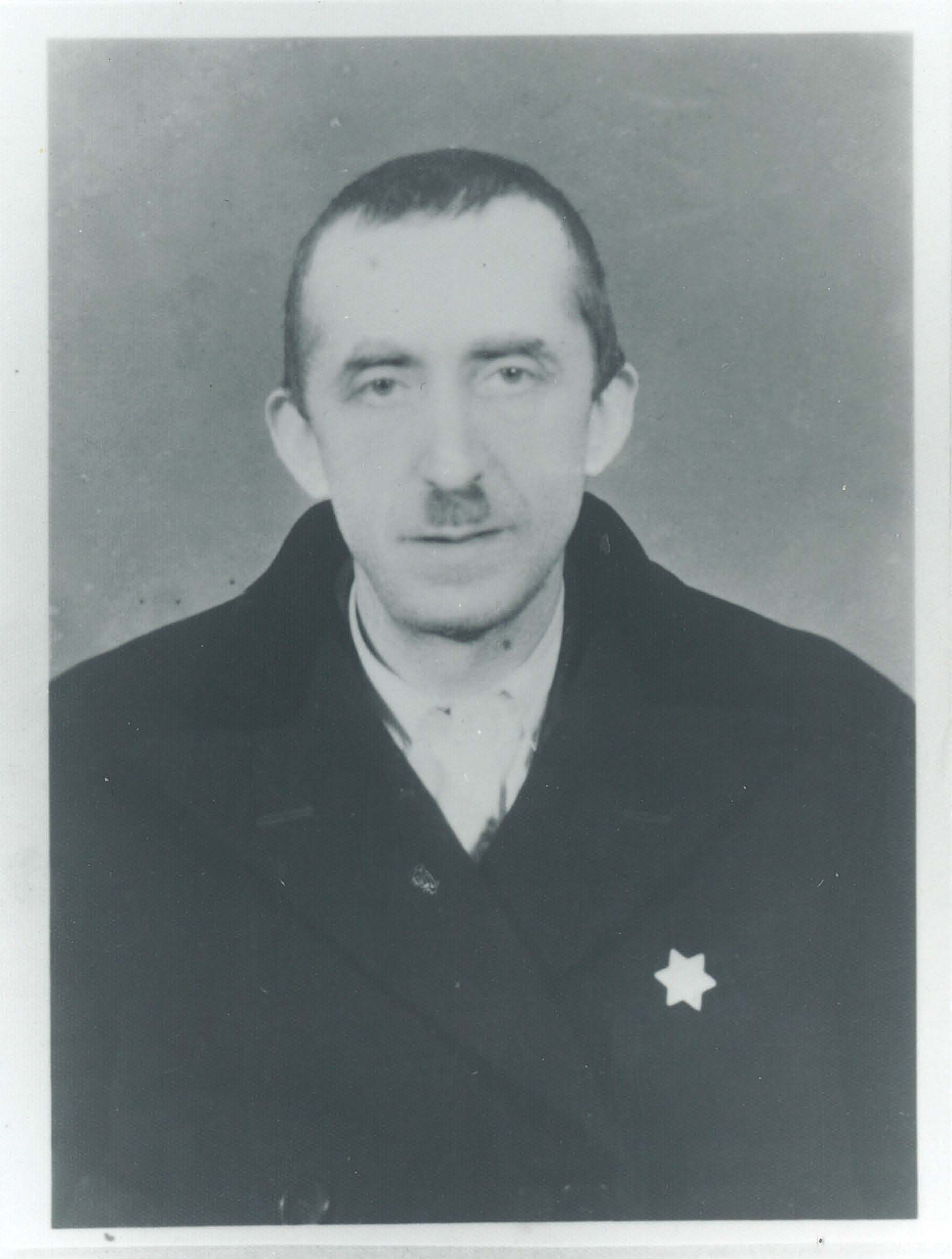

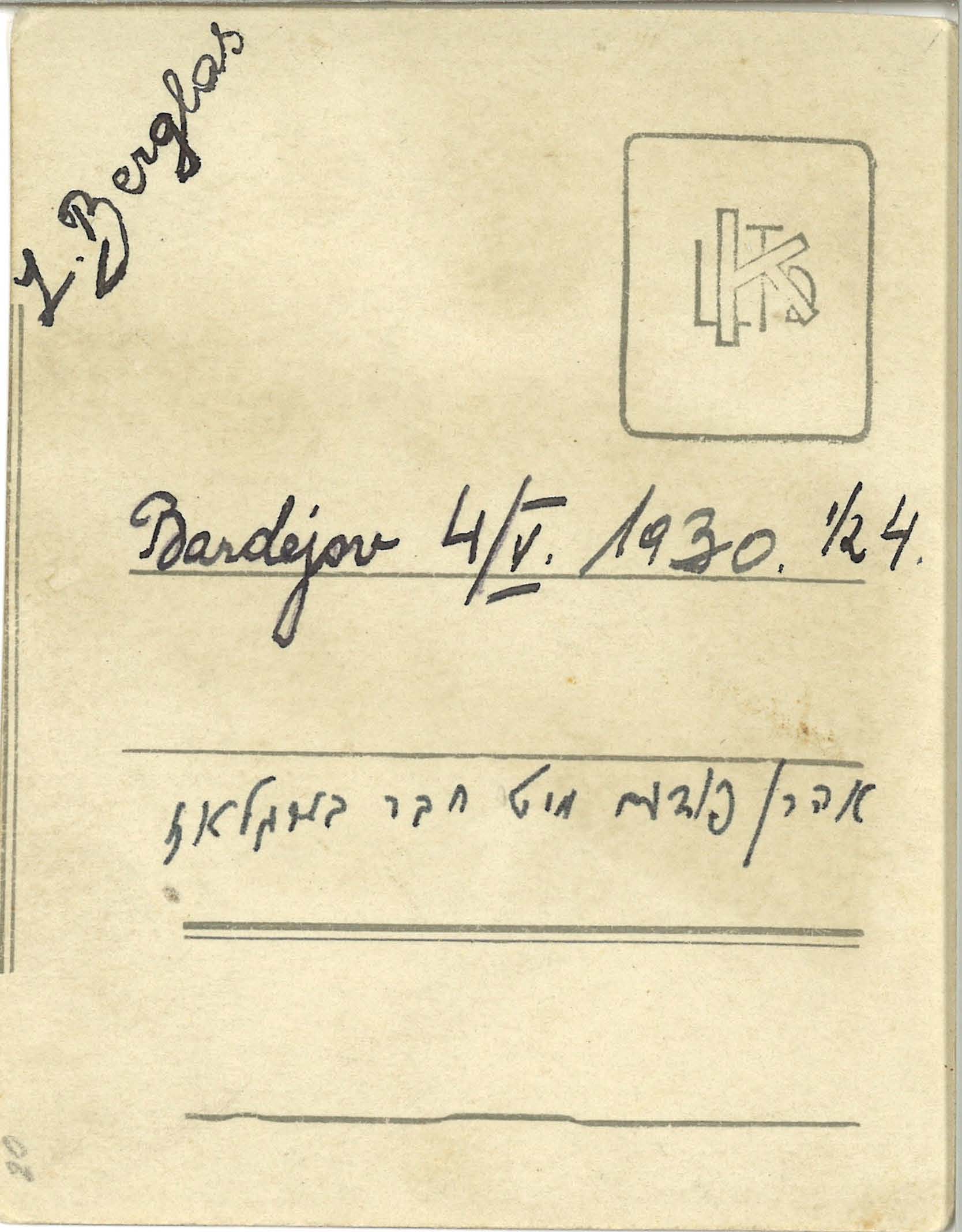

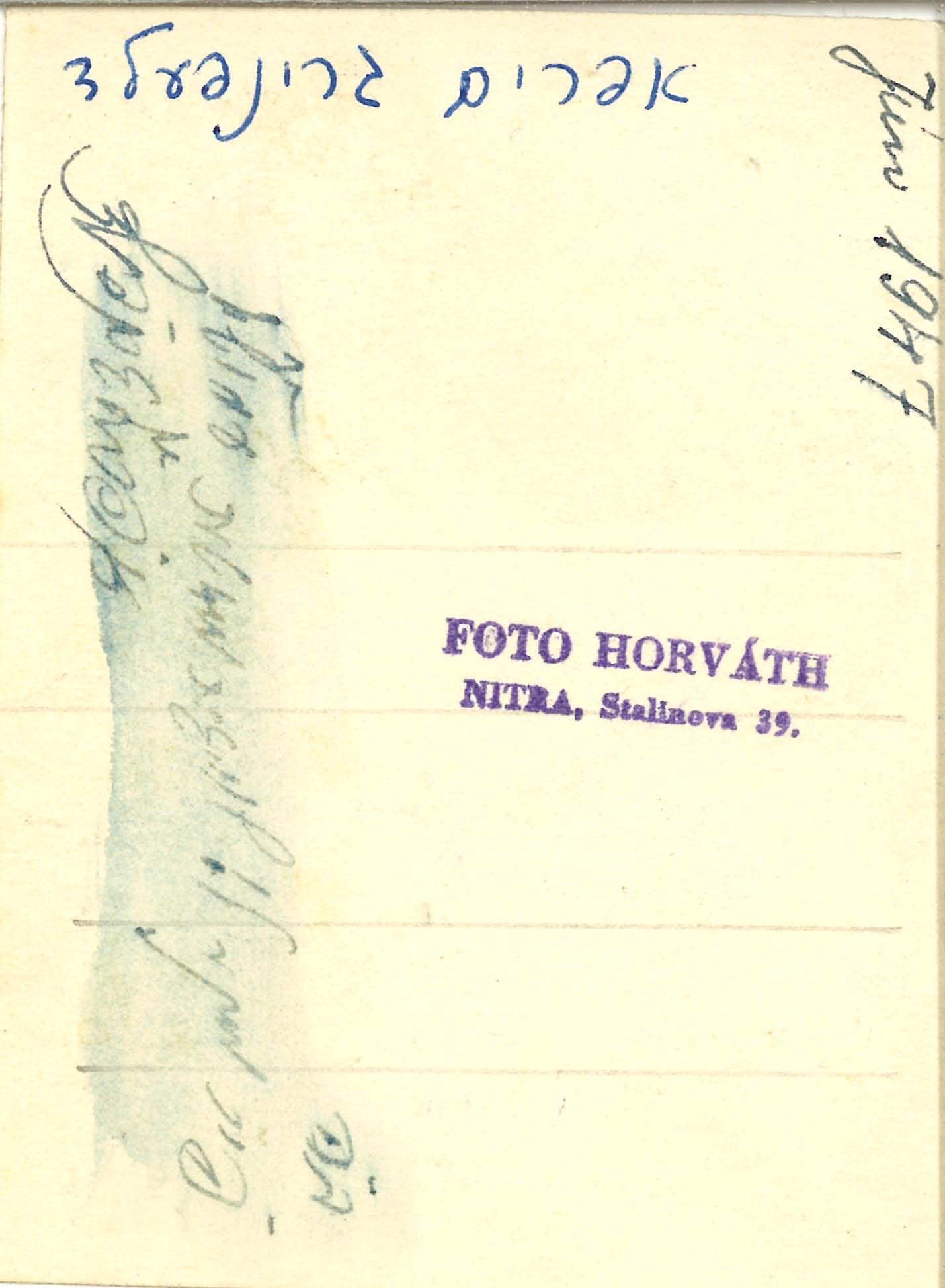

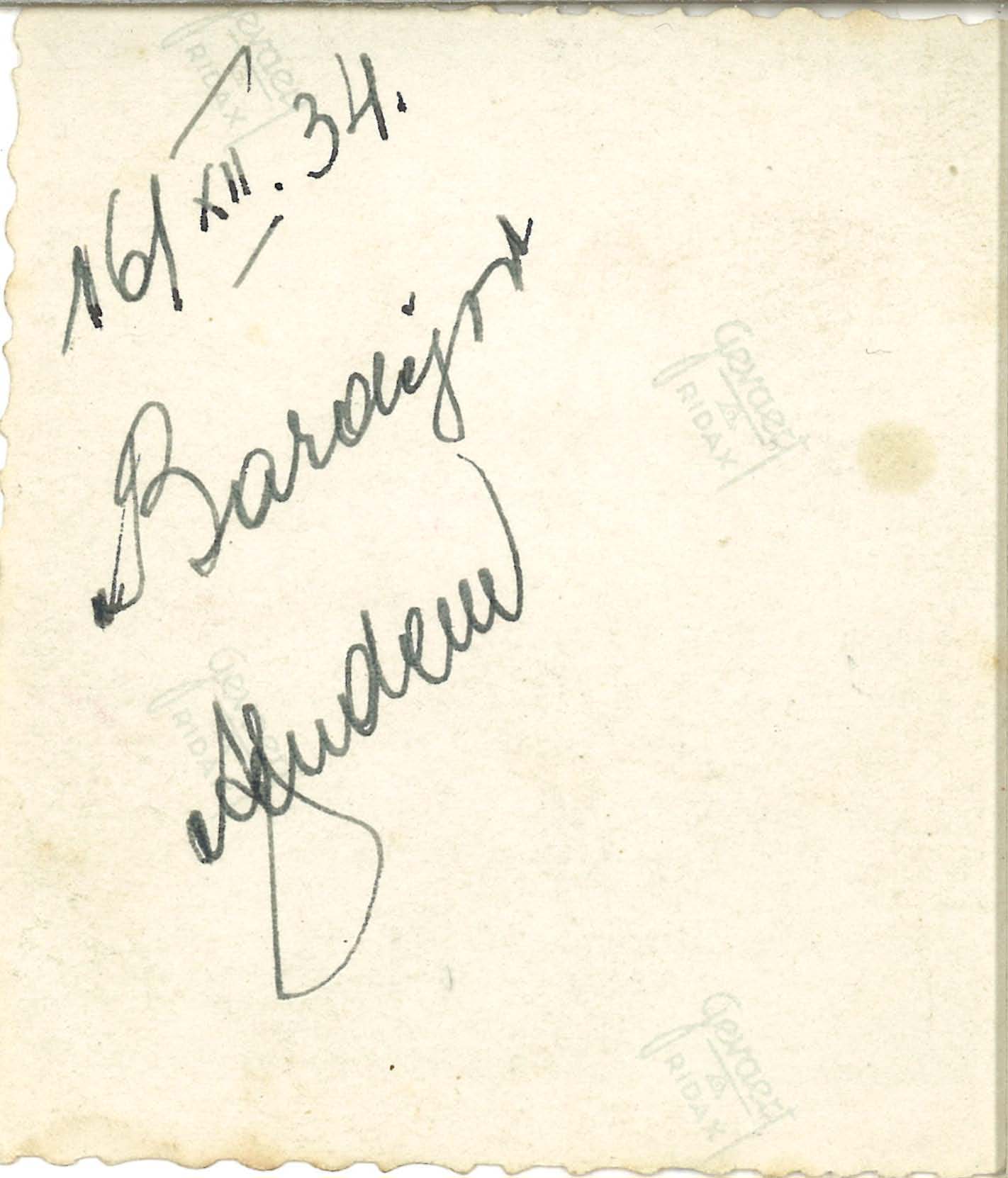

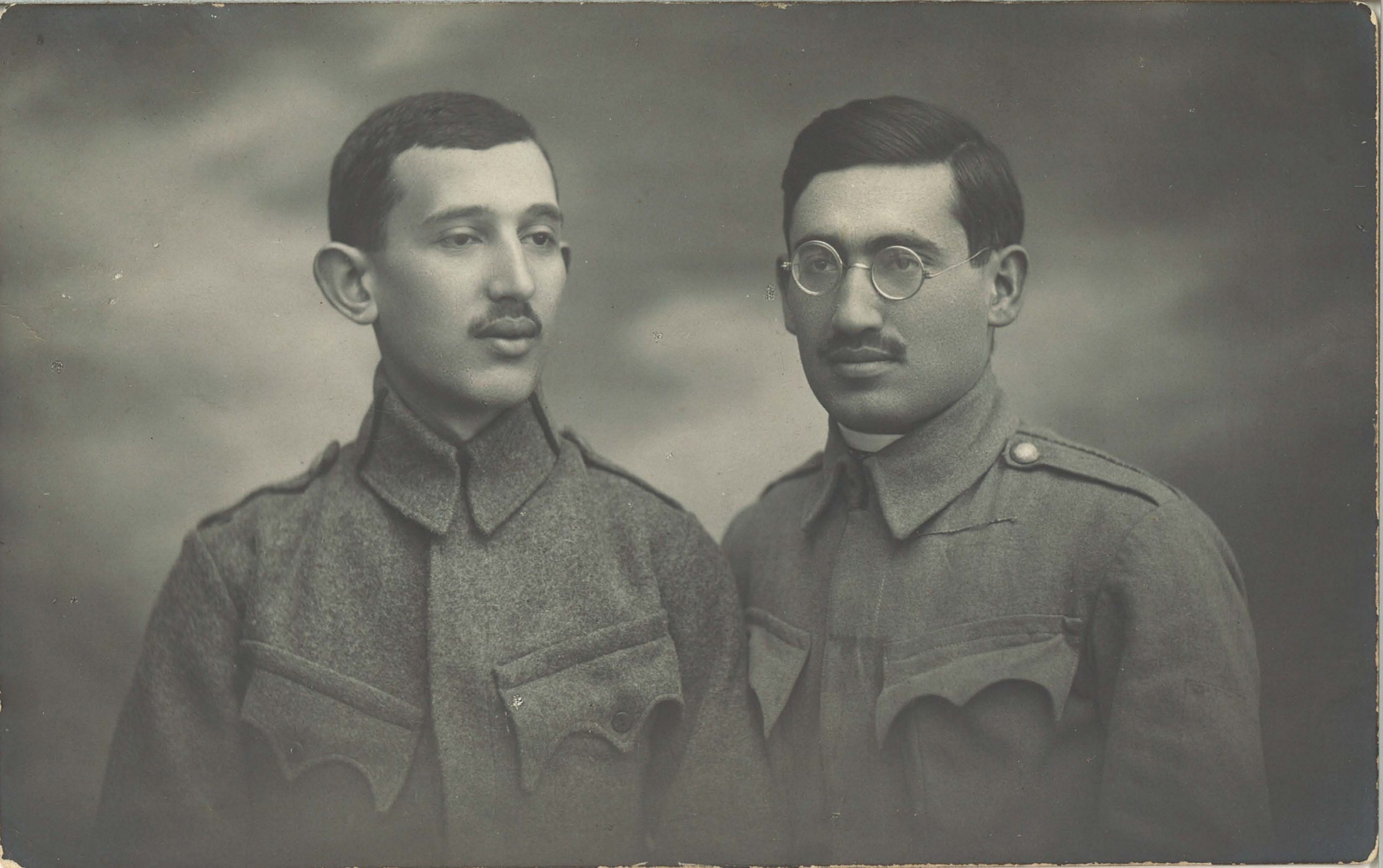

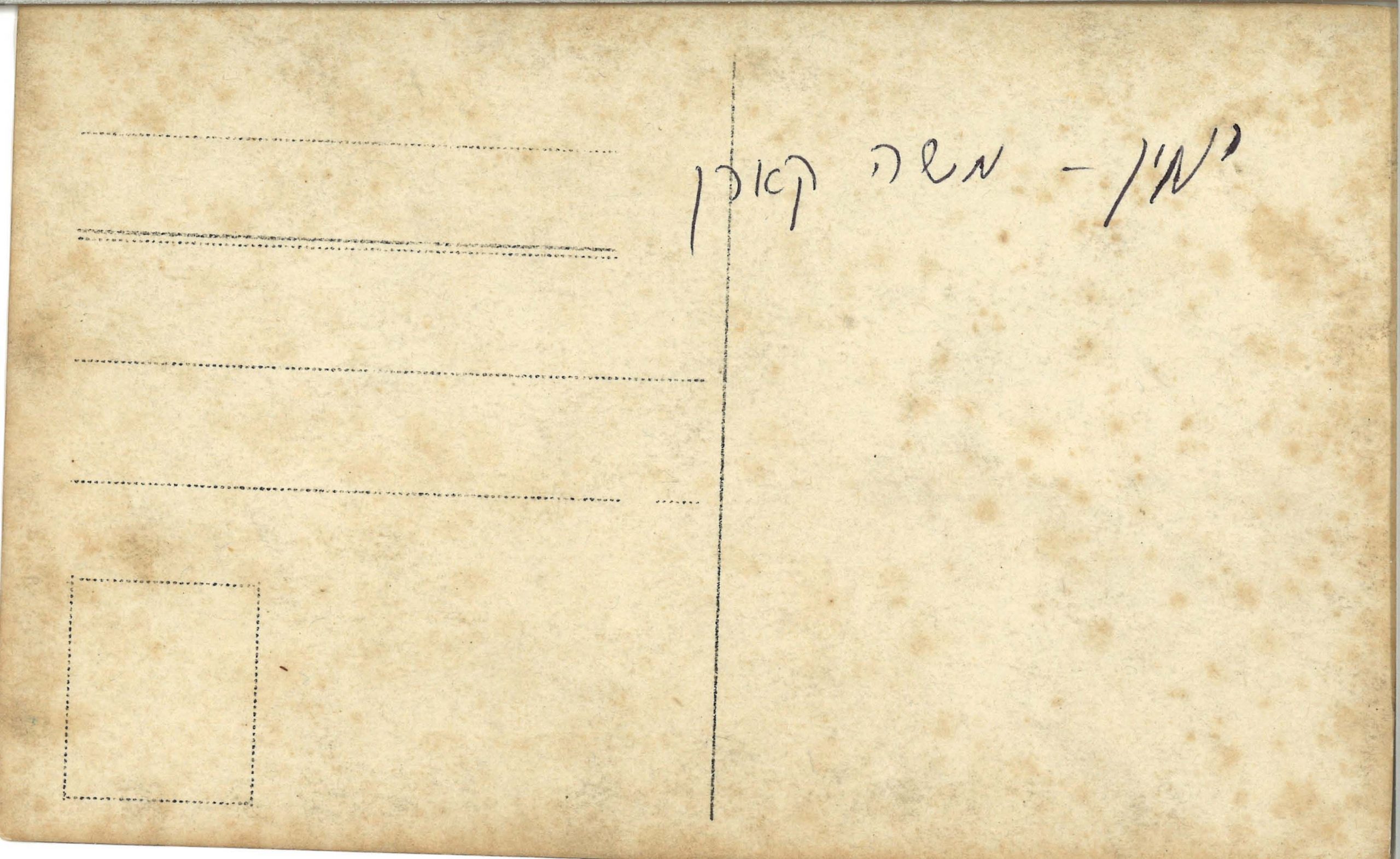

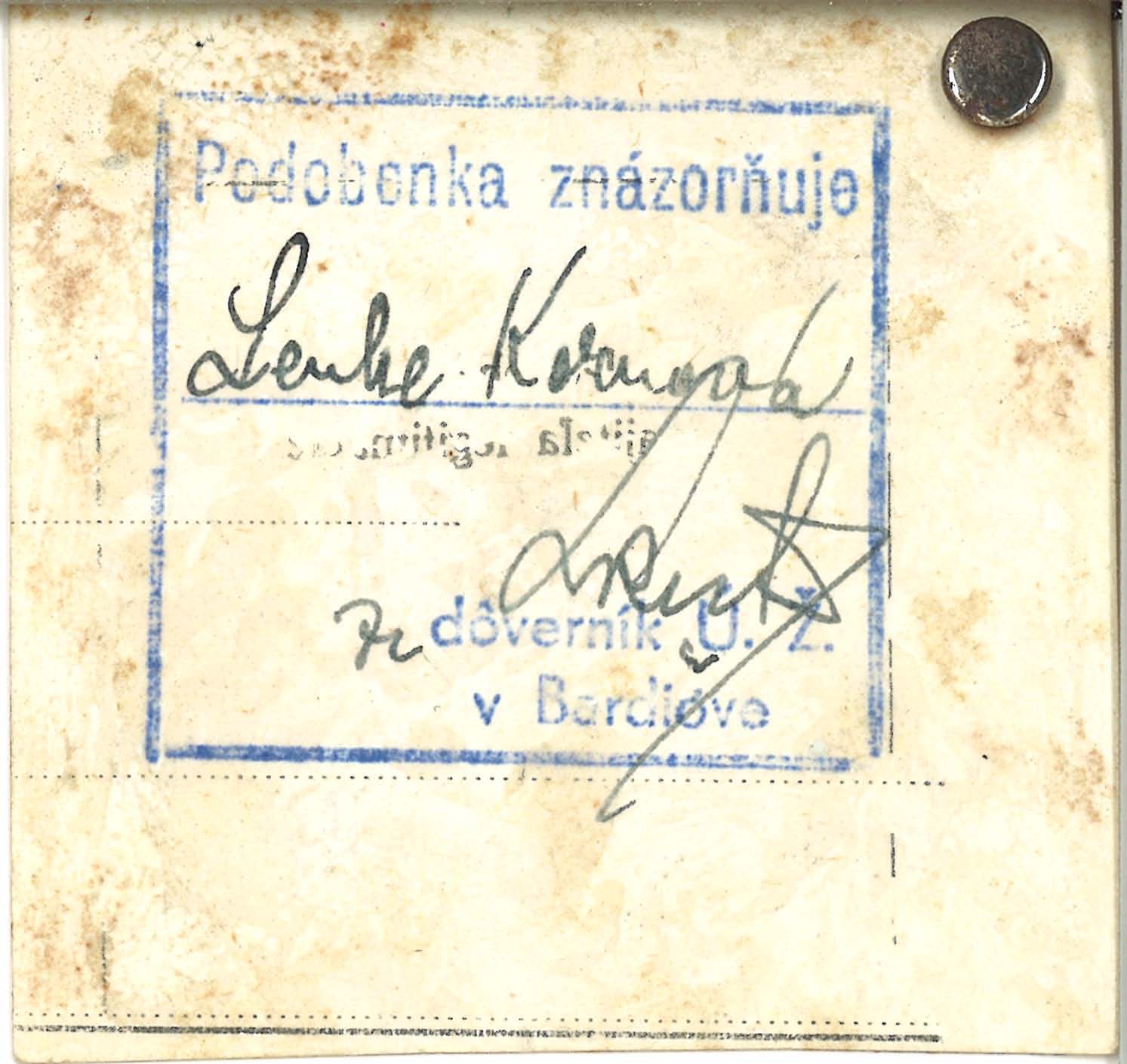

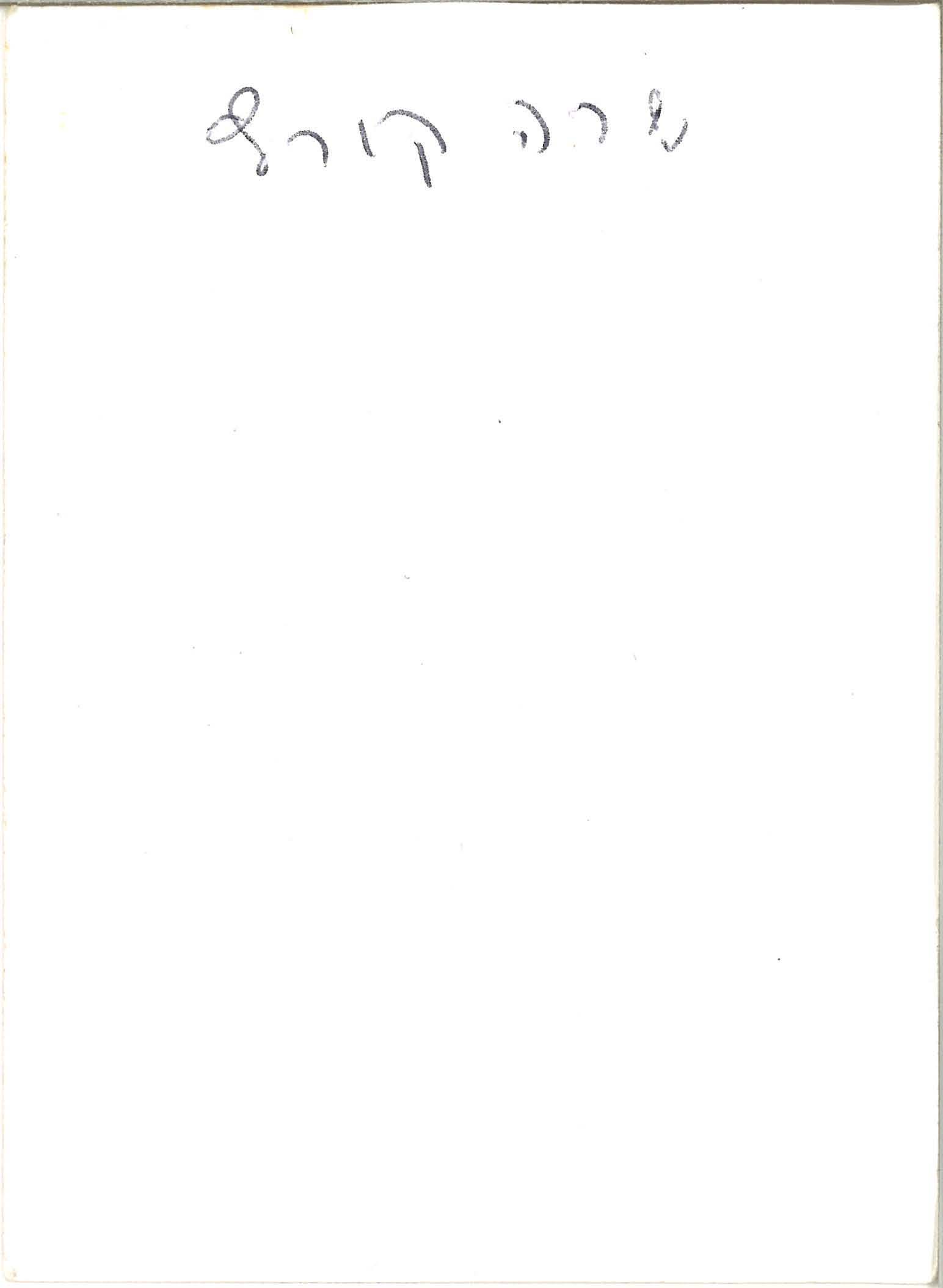

Since the deportation and destruction of the Jewish population of Bardejov during World War II, the stories of these citizens have been lost. It is our goal to resuscitate their stories and give proper credit to the legacy they left in Bardejov and the surrounding area.

We do this by collecting family histories from around the world, doing our own diligent research on the subject, and piecing together what we can about the past. One of our major projects includes a Memorial Book dedicated to the history of Bardejov and its Jewish inhabitants.

These stories are then infused back into the spaces and places that have undergone restoration. This helps return traces of the vitality and meaning to these sites. See our Cemetery restoration project below for a keen example.

SPACES

Because the Jewish population was, for many years, a substantial and important part of Bardejov society, there are many locations within the city that have significance for Jewish heritage.

However, many of these spaces have not been occupied or maintained by Jews since the second World War. Thus, they have either fallen into disrepair, or their meaning as a site of Jewish culture has been either diminished or erased entirely.

We have already successfully restored multiple sites in Bardejov, including the Old Synagogue and the Jewish Cemetery, and we continue to work to return the historical integrity of other sites such as the Beit Hamidrash and the Mikvah in the Jewish Suburbia.

You can read more about these projects by exploring below.

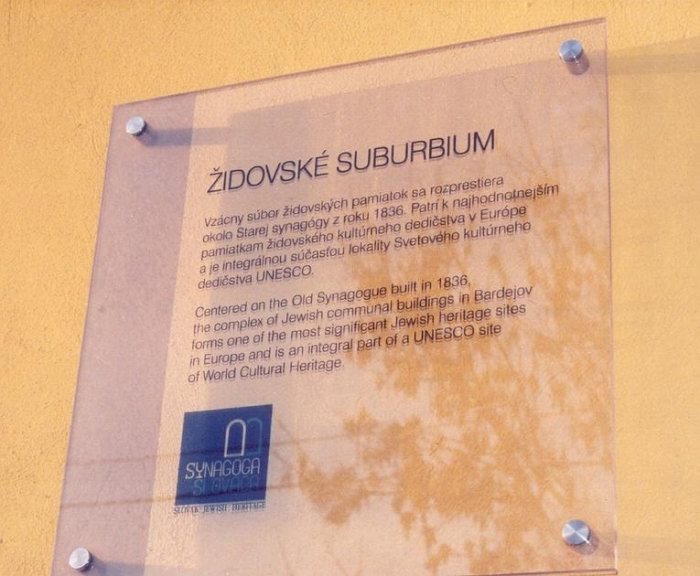

JEWISH SUBURBIA

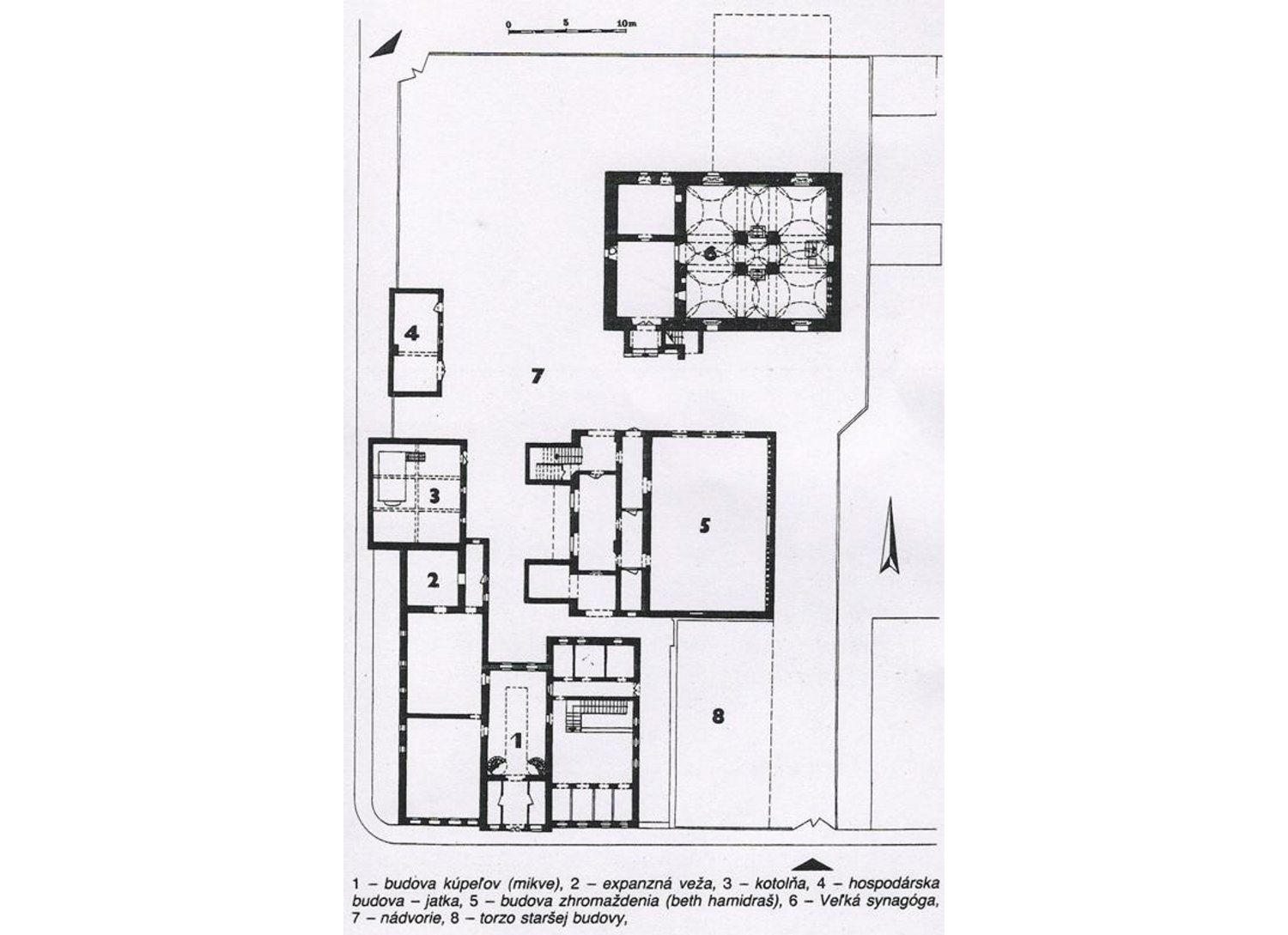

The historic Jewish quarter—Jewish Suburbia (in Slovak, židovské suburbium)—an example of Bardejov’s historic Jewish communal life, was built in the early 19th century according to Talmudic guidelines and includes:

A Jewish slaughter house once stood nearby on the spot which is now occupied by a supermarket.

UNESCO included the compound in its nomination of Bardejov as a World Heritage Site due to “its cultural and historical significance.”

The Old Synagogue has been restored and was opened to the public in July 2017. The Beith Hamidrash, has recently been vacated and is in the planning process towards restoration and the establishment of a Cultural-Educational Center and Museum.

The Mikvah, which until recently served as a building supply store, is now closed. We hope that the Mikvah will also be restored in the near future so that the Jewish Suburbia can be preserved in its entirety in recognition of, and as a memorial to, the Jewish communities that contributed to Bardejov’s social, economic, and cultural life throughout its history.

The impressive Bardejov Holocaust Memorial, adjacent to the Jewish Suburbia, was dedicated in an official ceremony in June 2014 and is open to the public.

New street sign to the Jewish Suburbia Complex in Bardejov, September 2022

OLD SYNAGOGUE

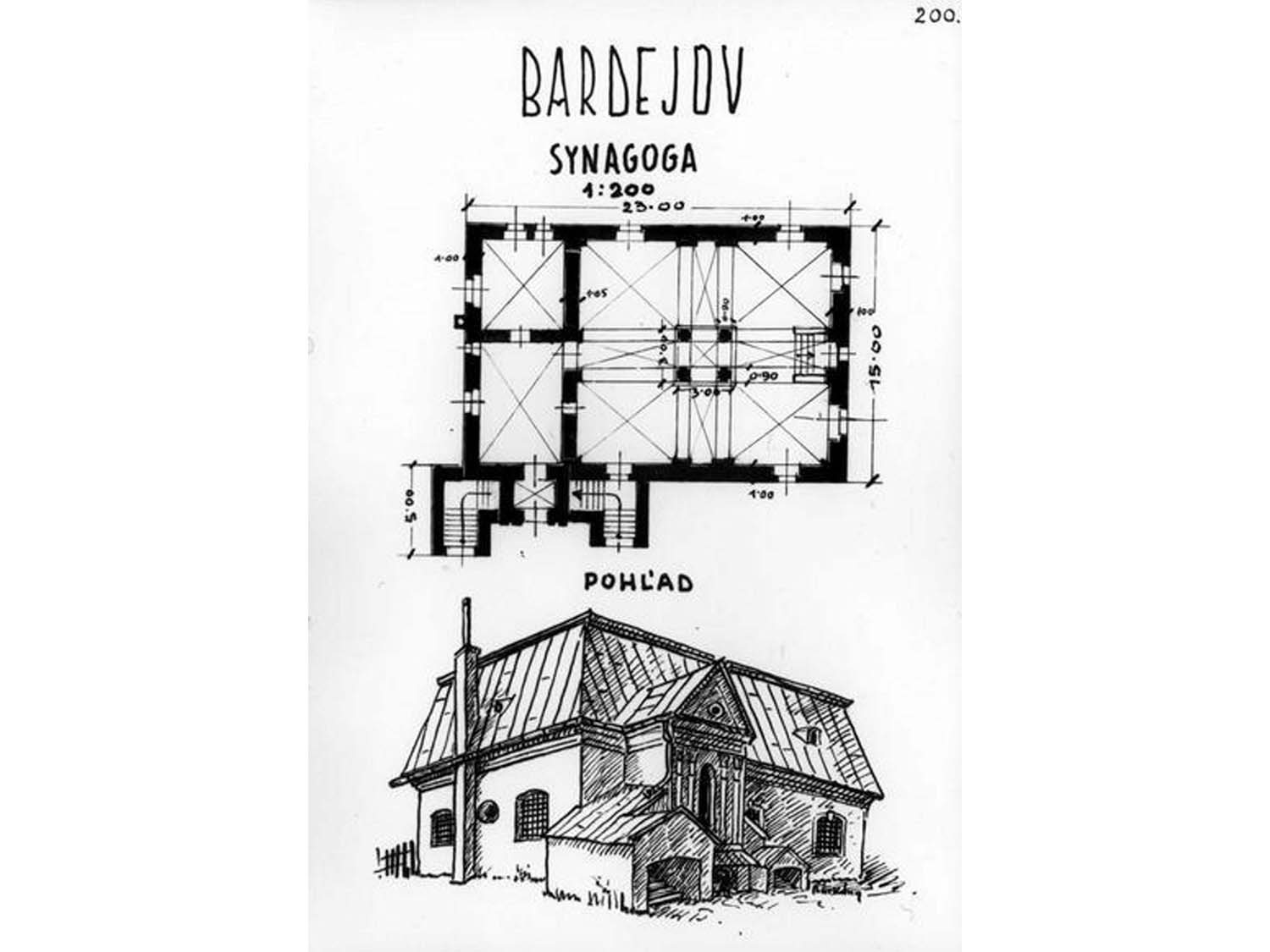

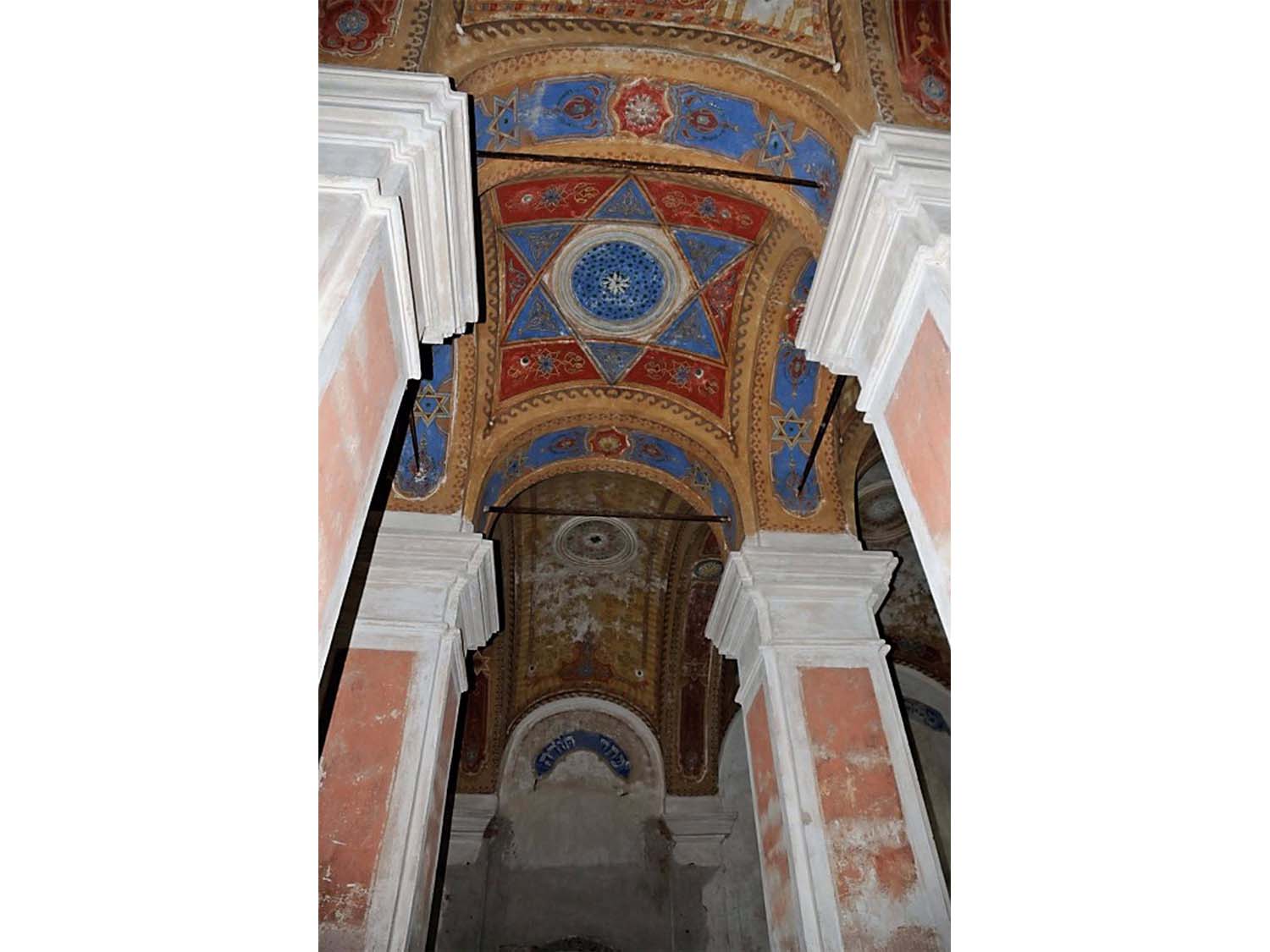

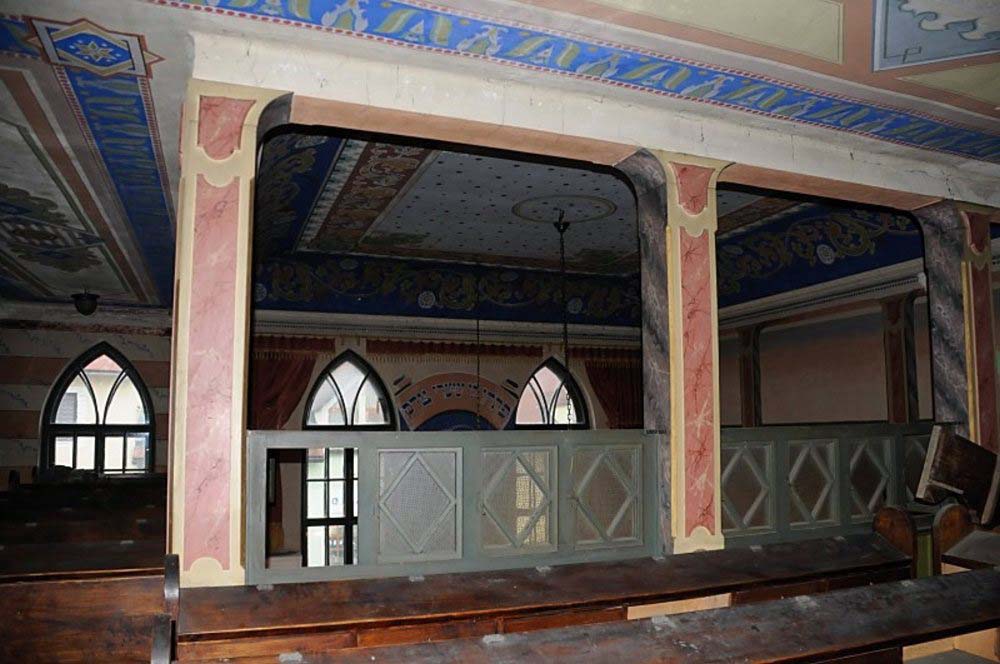

The largest and most famous of the pre-World War II synagogues in Bardejov is the Old Synagogue. Begun in 1829 and completed in 1836, it is the oldest building of the Jewish Suburbia. Reflecting architectural features of the Baroque and Neo-Classical styles, it is one of two remaining nine-bay synagogues in Slovakia (along with the synagogue in Stupava) and is considered one of the most valuable examples of synagogue architecture in the country.

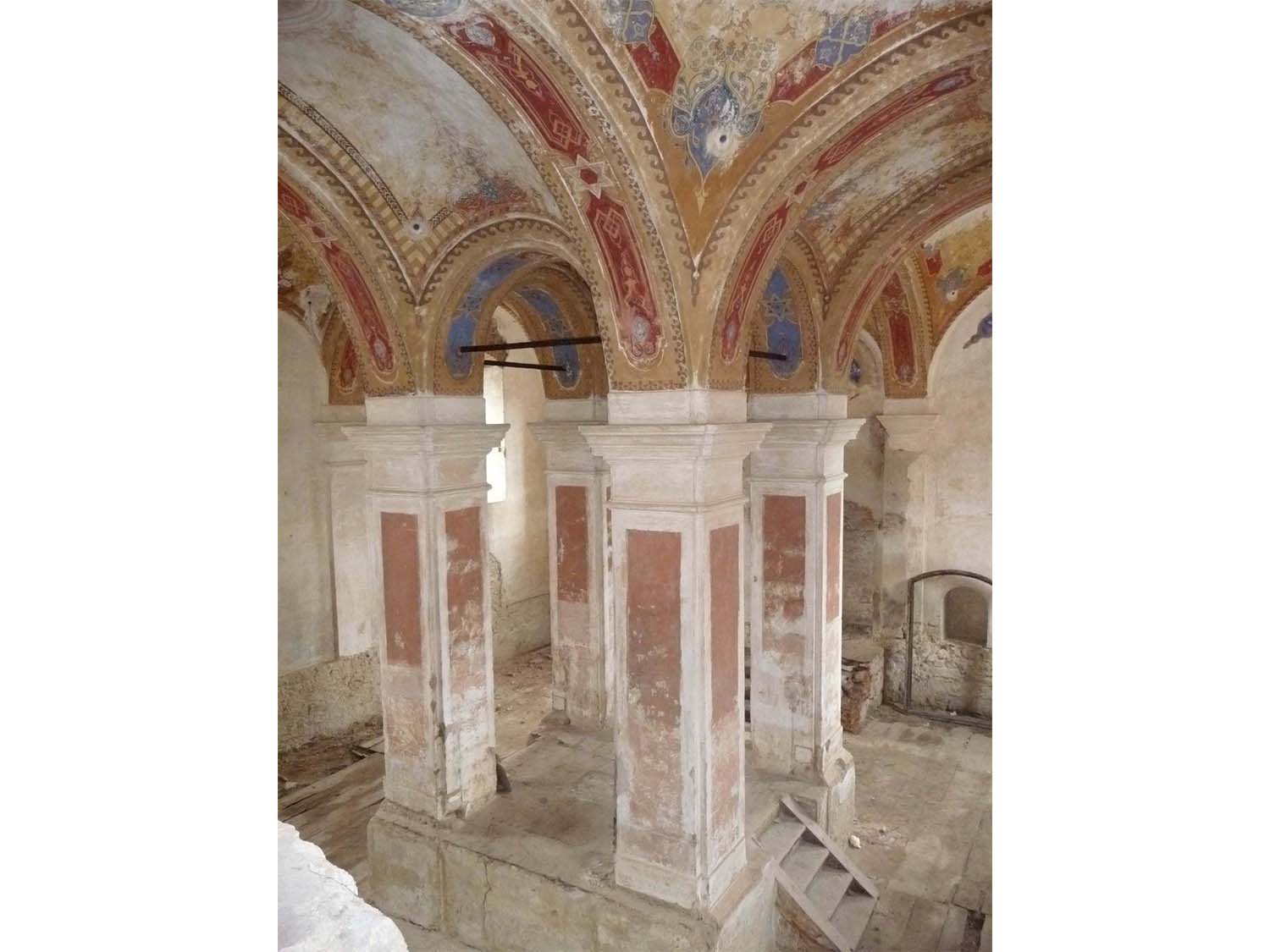

The Old Synagogue had been in great disrepair and used as a storage place for the merchandize of a plumbing and hardware business until it was empties in 2010. At that time some structure repairs to the roof and windows were performed as well as minor restoration of the ceilings.

In November 2014, the EEA and Norway Grants awarded 617,000 Euros to UZZNO for the restoration of the Old Synagogue in the Suburbia.

Restoration works began in the spring of 2015 and progressed rapidly. The Synagogue was officially opened to the public on June 2017.

OLD SYNAGOGUE AFTER RESTORATION

OLD SYNAGOGUE BEFORE RESTORATION

VIDEO ABOUT THE RESTORATIONby Vita in Suburbium

VISIT THE LINKS BELOW TO LEARN MORE

RESTORATION OF BARDEJOV OLD SYNAGOGUE IS COMPLETE!

by Jewish heritage Europe

RESTORATION PROJECT DETAILS

by Židovské suburbium Bardejov

OLD SYNAGOGUE BROCHURE

by Vita in Suburbium

OLD SYNAGOGUE PHOTO GALLERIES

by Židovské suburbium Bardejov

BEIT HAMIDRASH

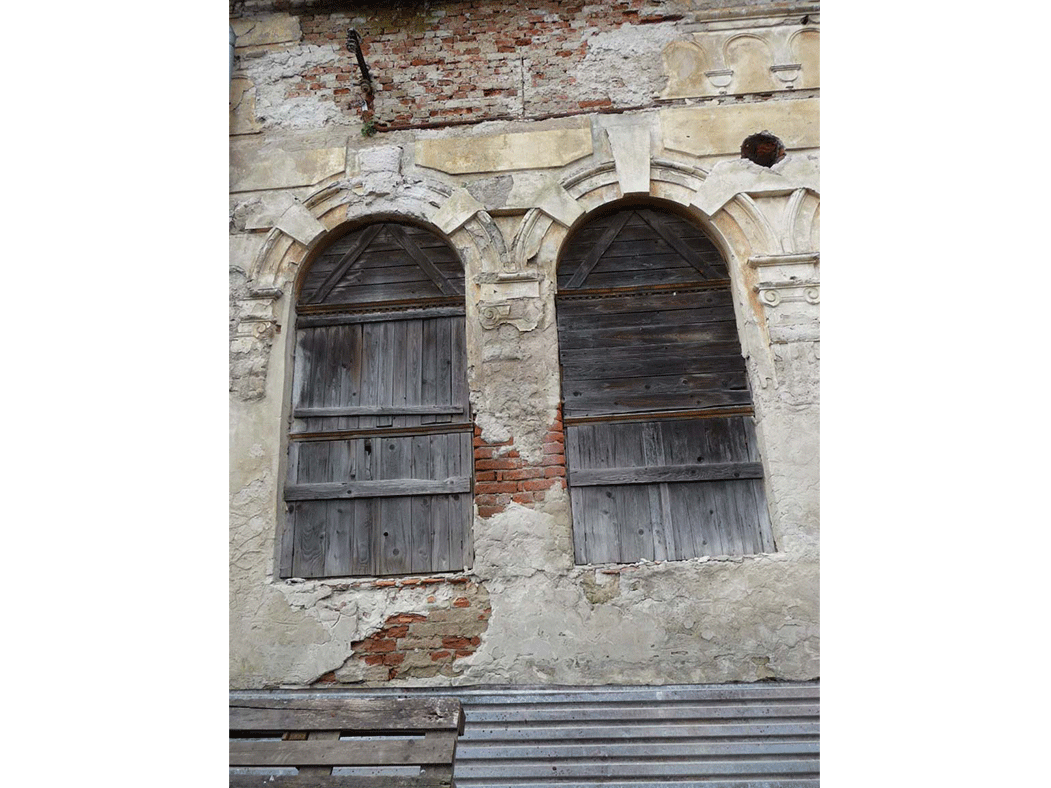

The Beit Hamidrash building, which was built in the late 19th century, served as a place for Torah study and as a prayer hall. Until a few years ago, the beautifully ornamented building was used as a storage facility for the building supply company that occupied the Suburbia. Discussions were underway between the City of Bardejov, the Bardejov Jewish Preservation Committee, local Bardejov advocates, and the Central Union of Jewish Communities in Slovakia (UZZNO) to vacate the Beit Hamidrash and create a museum dedicated to Bardejov’s Jewish history.

As a result of the ongoing cooperation with UZZNO, Beit Hamidrash was vacated in June 2016 and restoration work began at the end of 2022. The construction concluded at the beginning of 2024, and now we are proceeding with the planning of a local Jewish Heritage Museum as part of the development of the Jewish Suburbia as an educational and cultural center.

BEIT HAMIDRASH: MUSEUM CONSTRUCTION PROCESS

Photos Courtesy of Miroslav Lissy and Milo Olejar

BEIT HAMIDRASH: BEFORE & AFTER BEING VACATED

MIKVAH

The Mikvah—ritual bath—dates from the late 19th century and is the front building of the Jewish Suburbia complex facing Dlhý Rad Street. It was previously used as a hardware store by the same company that occupied the Beit Hamidrash. Its exterior was renovated in 2009 by the tenant. A Holocaust memorial plaque was placed on the Mikvah’s façade in 1992.

Discussions were underway between the City of Bardejov, the Bardejov Jewish Preservation Committee, local Bardejov advocates, and the Central Union of Jewish Communities in Slovakia (UZZNO) to vacate the Mikvah and the Suburbia’s grounds and restore the complex in its entirety so that, together with the Holocaust Memorial built to honor Bardejov’s lost Jewish community, and the newly renovated Beit Hamidrash, these buildings can become a cultural and educational center for both Jews and non-Jews. The Mikvah was vacated in 2021.

MIKVAH BEFORE AND AFTER RENOVATION

BIKUR CHOLIM

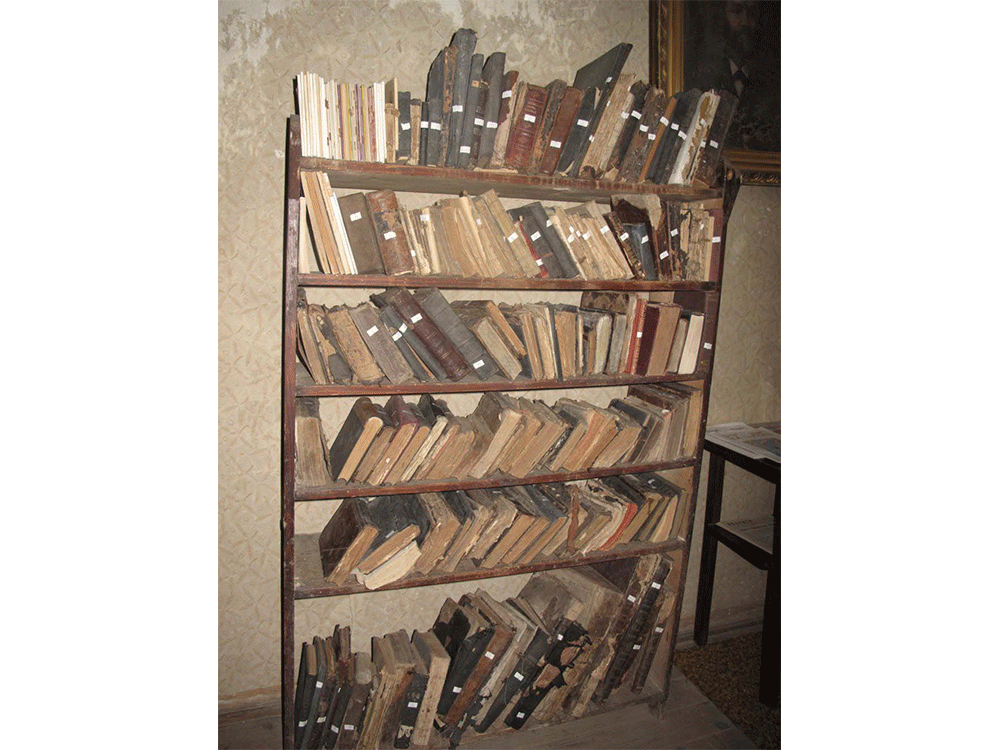

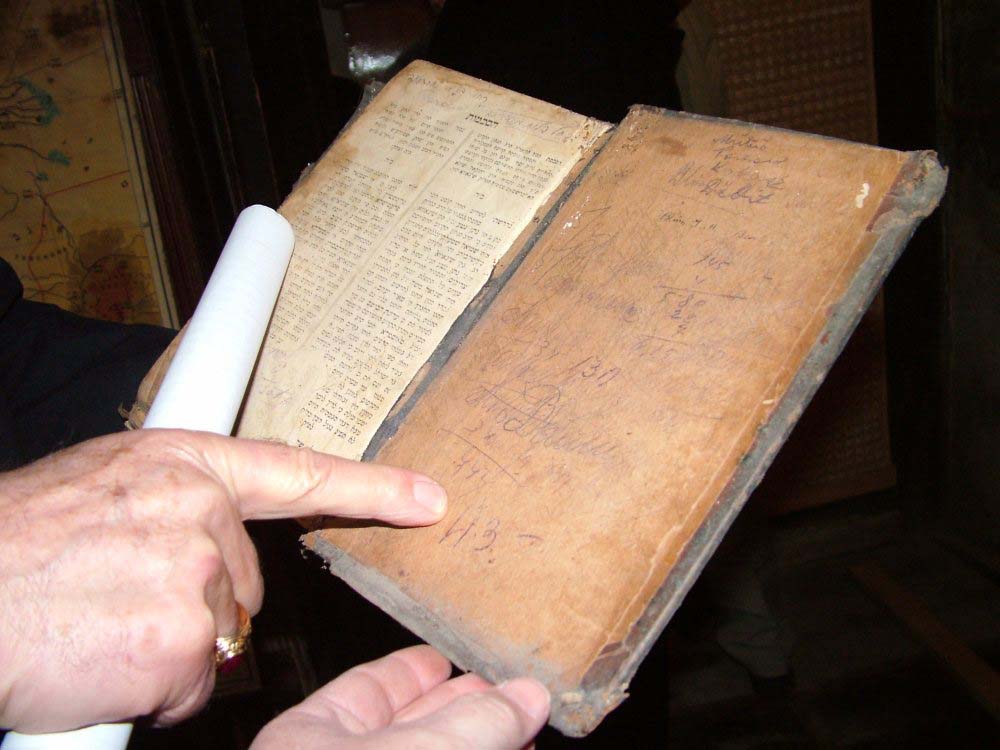

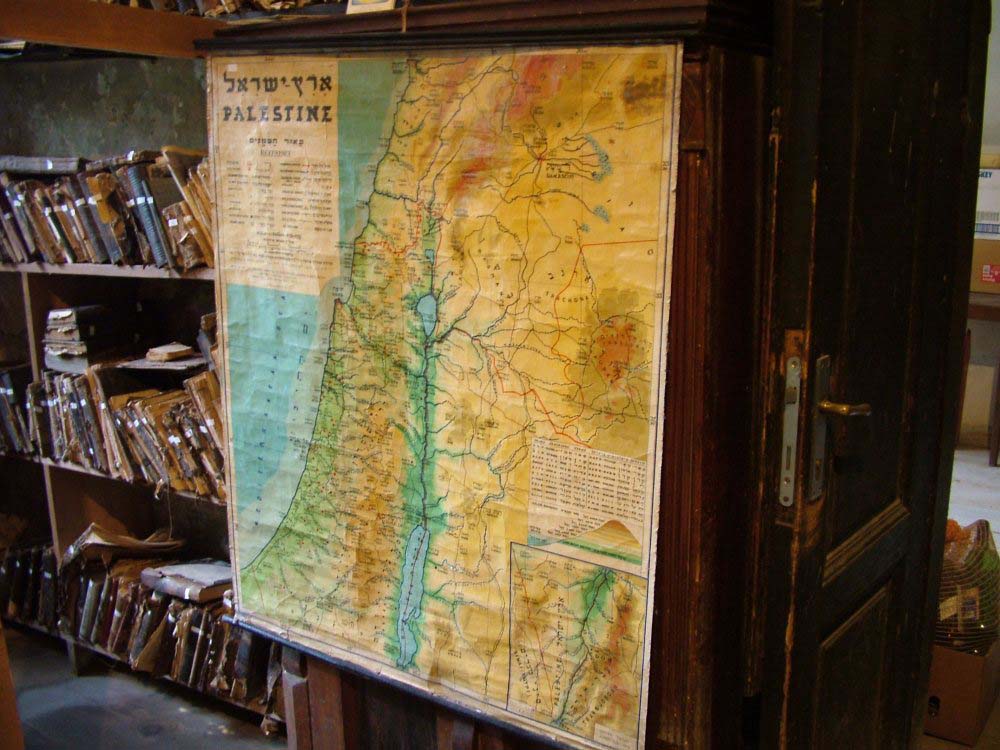

Chevra Bikur Cholim Synagogue is an example of a well-preserved prewar synagogue. Its interior furnishings are fully intact. The synagogue was established in 1929 by the Chevra Bikur Cholim, a Jewish charitable association. It is located in the city center on Klastorska Street, near the market square. The eastern façade of this simple building faces the street. A pair of pointed windows marks the sanctuary. To the right of the façade is a gateway with a smaller pointed window above. The interior, while narrow, extends toward the back of the lot and leads to a backyard.

During the Nazi occupation, a Christian woman, Mrs. Maria Koperniechova, lived in the synagogue. She bricked up the windows to hide the synagogue’s appearance and refused entry to soldiers. Today, Chevra Bikur Cholim is Bardejov’s only synagogue that was not violated and that remained fully intact during the war, including its prayer books and other Jewish artifacts. After the war and up until his death in 2005, Mr. Meyer Špíra, one of the last Jewish residents of Bardejov, maintained the building and prayed in its sanctuary. Thanks to his efforts, the synagogue’s interior is considered one of the best preserved in Slovakia.

During the Memorial Gathering in 2012, the Bardejov Jewish Preservation Committee recognized Meyer Špíra posthumously for his work in maintaining and caring for the synagogue. The Committee also recognized Mrs. Koperniechova with a “Righteous of Bardejov” award for saving the synagogue during the Nazi occupation. The synagogue is currently maintained by the Central Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Slovakia (ÚZŽNO).

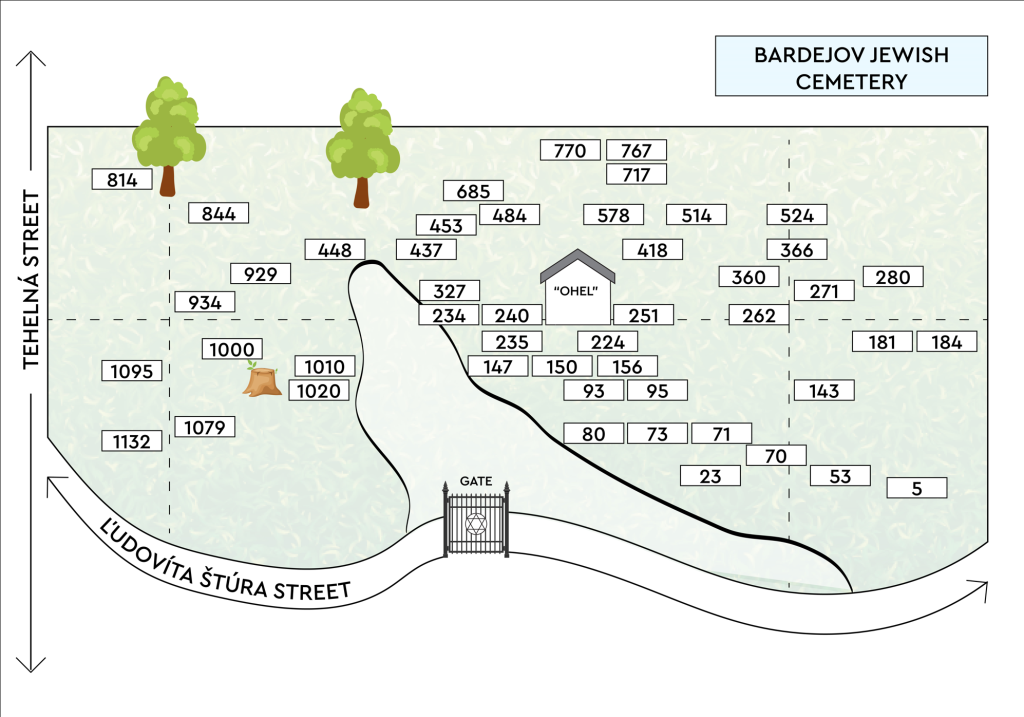

THE JEWISH CEMETERY

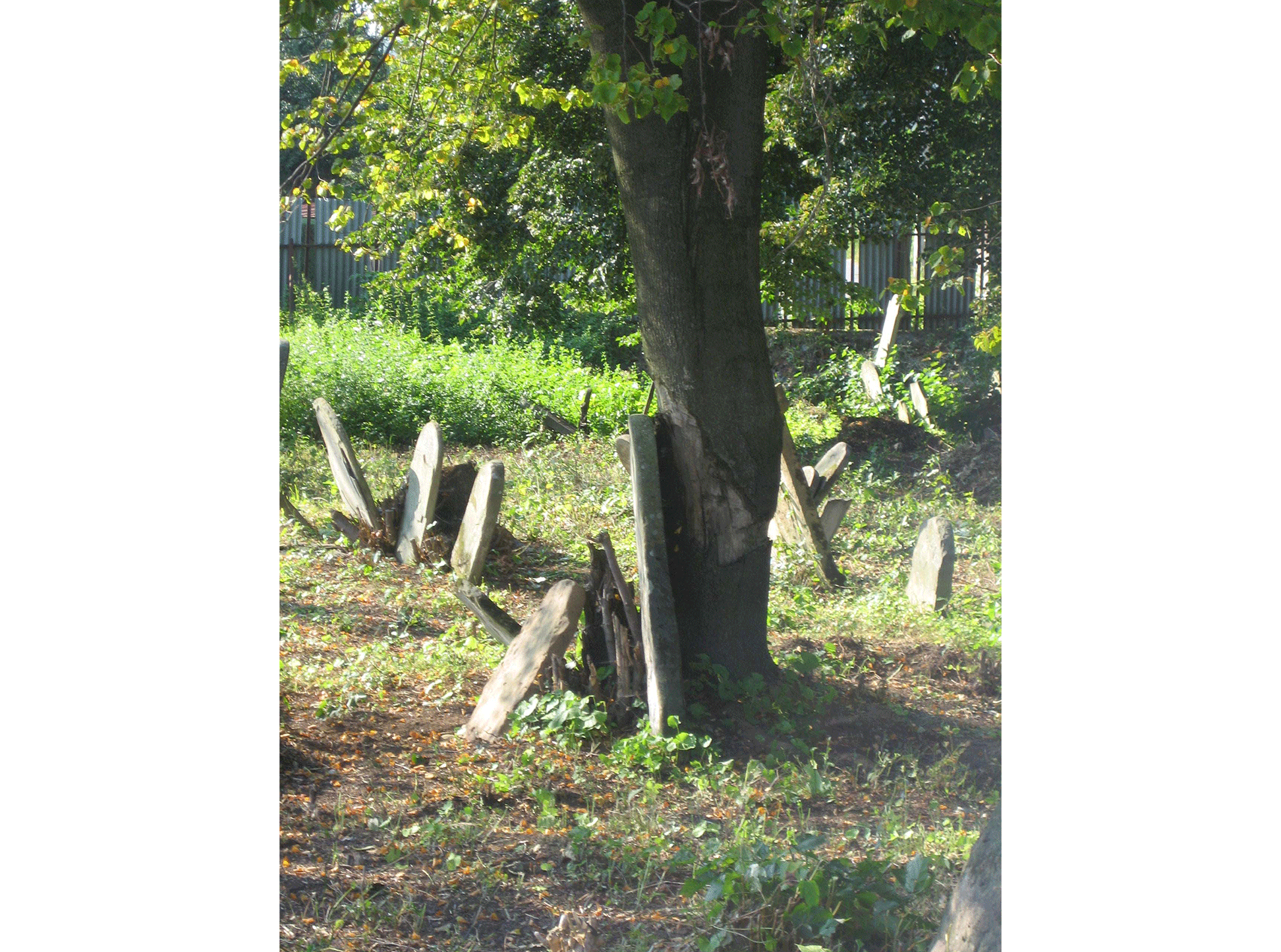

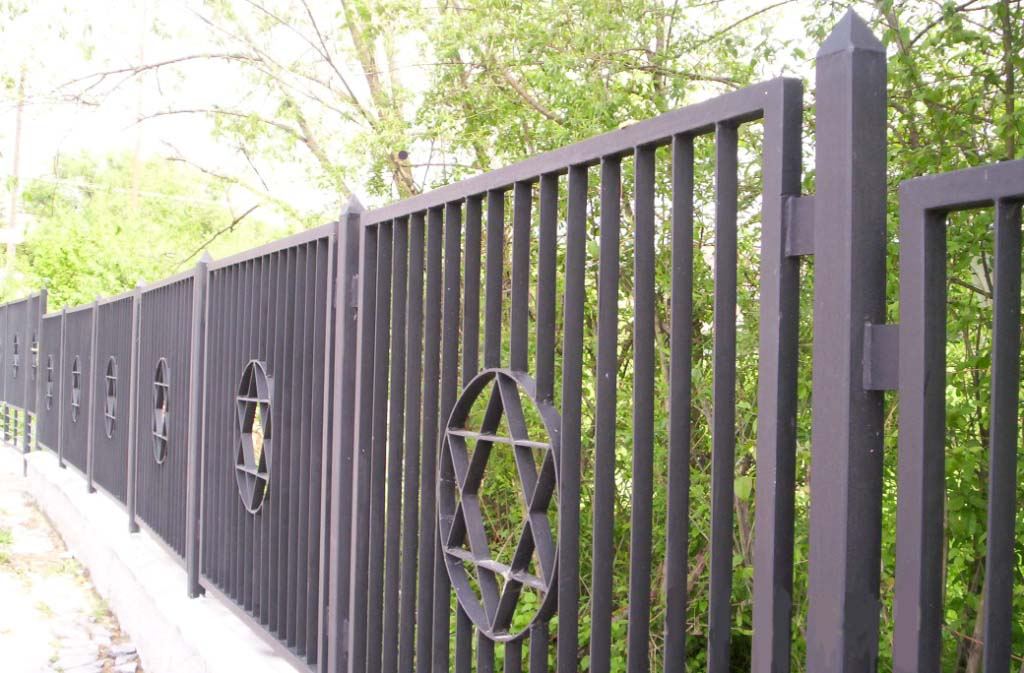

Bardejov’s isolated, urban Jewish cemetery is located on a hillside directly off a public road with adjacent commercial and residential properties. The decorative, wrought-iron fence encloses 1,288 gravestones from the18th– to 20th-century. The stones are constructed from marble, granite, limestone, sandstone, and other materials and are either finely smoothed and inscribed or carved with relief decoration.

RESTORATION PROCESS

Phase 1: Prior to August 2005, the grounds were overgrown and inaccessible. Every gravestone was in disrepair. In August 2005, Phase 1 of the restoration – clearing the grounds and make them accessible- began.

Phase 2: By 2008, new concrete foundations were laid; many of the 1,288 stones were straightened, re-cemented, or re-erected, including some stones in the Ohel; the graves and headstones were photographed and cataloged by the Heritage Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Cemeteries (HFPJC) and were posted on our Matzevah Database and Matzevah Photo Gallery. A Matzevah Index document was also created (please do not reproduce).

Phase 3: In 2009, a new fence was erected around the entire perimeter of the cemetery, replacing the former, unsightly concrete, metal, and brick one. The new black wrought-iron fence features decorative Star of David motifs in the center of each section. The cemetery is maintained regularly. A resident of Bardejov has a key and opens it to visitors upon request.

CEMETERY ADDRESS

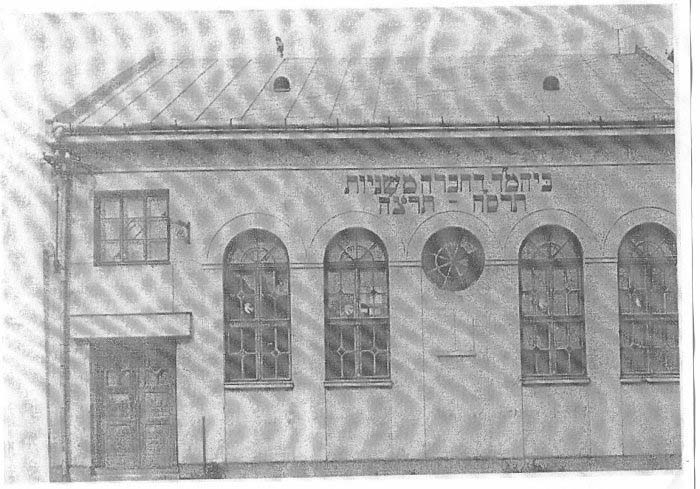

CHEVRA MISHNAYOT

Chevra Mishnayot Synagogue was built in 1905 by the Jewish community’s Mishnah study association. It is located on Stocklova Street, in the city center on the other side of the market square. The building was repurposed in the 1960s as a secondary school of commerce. It was later occupied by a bakery, then served as an office building, and now houses various establishments such as a hair salon and a health food store. In 2016 the exterior of the building was repainted. There is no plaque identifying the building’s important role in Bardejov’s Jewish history. Click here to read more about the building’s history.

BARDEJOV JEWISH HISTORY

Early History: The well-preserved, historic town of Bardejov, formerly Bártfa (Bartfeld in German and Yiddish) was settled in the early Middle Ages along an ancient trade route between the Baltic and the Black Seas. Throughout the 13th and 14th centuries, Bardejov was one of the leading towns in Hungary. By the 15th century, it was at the height of its economic development, due primarily to the manufacturing and trade of linen. With a population of approximately 3,000, it registered more than 50 guilds. By the 16th century, architectural developments had further enhanced the town, including the completion of a parish church and a town hall in the center of the main square. During this period, Bardejov made significant advances in culture and education, including the construction of a Latin public school, a public library, and printing houses. In the mid-1700s, the mineral springs in the area—known for their healing properties since the 13th century—were developed into the Bardejov Spa. Over the centuries, the spa was expanded and modernized and by the end of the 19th century it had become one of the most renowned in Europe.

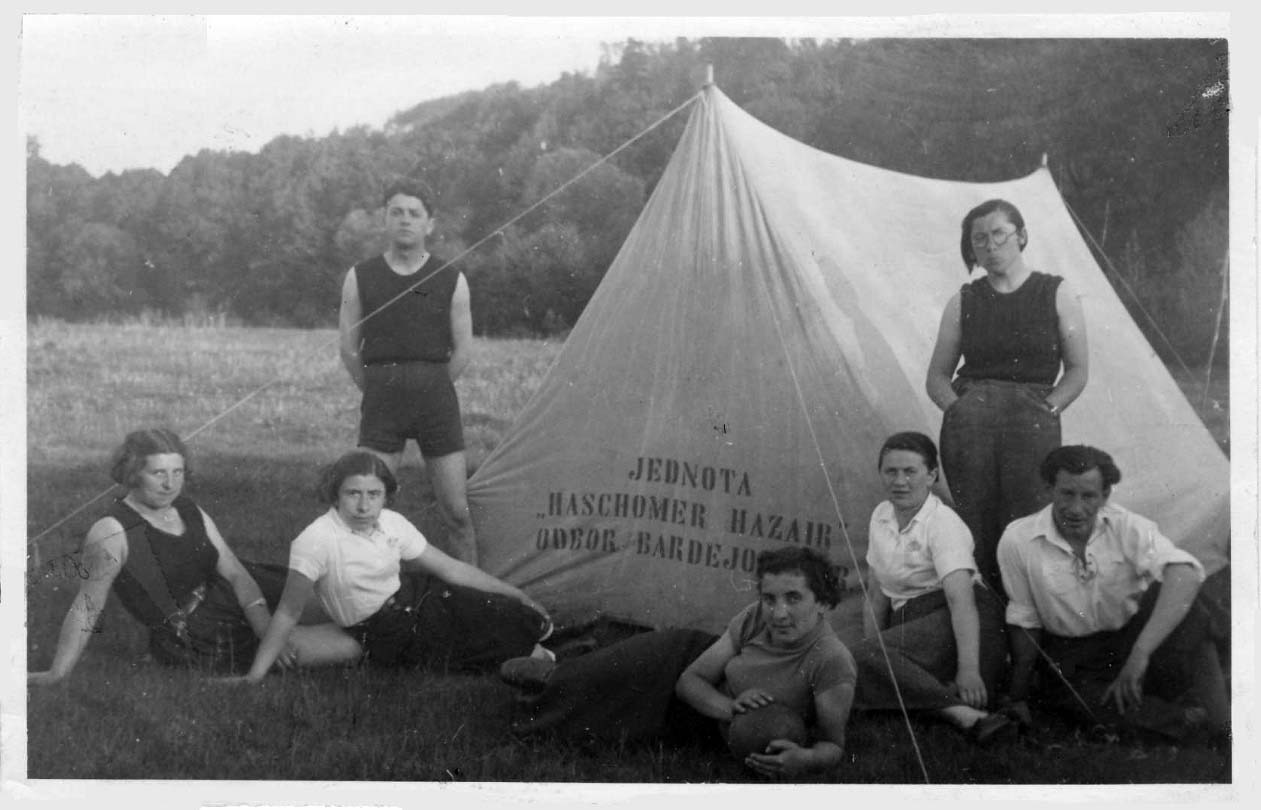

The presence of Jews in Bardejov dates from the early Middle Ages. Expelled from Bardejov in 1631, Jews from Galicia resettled there in the mid-18th century. These descendants of the Galician Hasidic dynasty founded by Rabbi Chaim Halberstam lived northeast of the marketplace and worked initially as farmers in nearby villages. By 1806, they began to establish community buildings. Eventually they built a thriving, self-contained complex north of the town center, which is known today as the Jewish Suburbia. It was outside the city walls, where Jews were allowed to live.

In 1869, after some restrictions against the Jews were lifted, the Jewish population grew to 1,011 (out of a total population of 5,307). At that time, Jews were not restricted to live only in the Suburbia area. Most were store owners, businessmen, and artisans. The Jewish community contributed to the overall economy of the town—including the development of Bardejov as a health resort—and to its distinguished printing history.

By 1900, Bardejov’s Jews had established a Hebrew printing press, becoming one of the last centers of Hebrew printing to be established in Europe before the Holocaust. From 1900 to 1938, two Hebrew presses printed over 100 volumes. Nearly all were rabbinic or Hasidic texts, reflecting the town’s cultural and religious distinction as the seat of one branch of the Halberstam Hasidic dynasty.

By 1919, Bardejov’s Jewish population had reached 2,119, with 40 settlements surrounding the Jewish quarter and united under the local rabbinate. Although by the 1940s Jewish children attended public schools and there were a large number of Jewish municipal council members, most of Bardejov’s Jews maintained an Orthodox way of life, praying in numerous synagogues established in the town.

In 1940, laws against Jews were enforced. Many of the town’s Jews had been pushed out of their businesses by the Slovakian state; Jews from the surrounding areas were brought to Bardejov. The 1942 mandatory census of the Jews, “Supis Zidov,” lists 3,589 Jews in the Bardejov region, of which 2,498 lived in the City of Bardejov. Their deportation began in March 25. On May 15, 1942, about 2,500 Jews were deported from Bardejov’s train station to concentration camps. A few Jews with “valuable professions” stayed, but by September 1944 they, too, were either deported or fled.

After liberation by the Soviet army in January 1945, seven Jews emerged from their hiding place in a wine cellar of a store in the main square. Some Jews returned from the Polish forests. The town became a center for refugees and for immigration to Palestine. In 1947, there were about 380 Jews in Bardejov, including 80 children; almost all of them left by 1959. In 2005, the last Jew living in Bardejov, Meir Spira A”H, died.

After more than 260 years of continuous Jewish presence, no Jews live in Bardejov today.

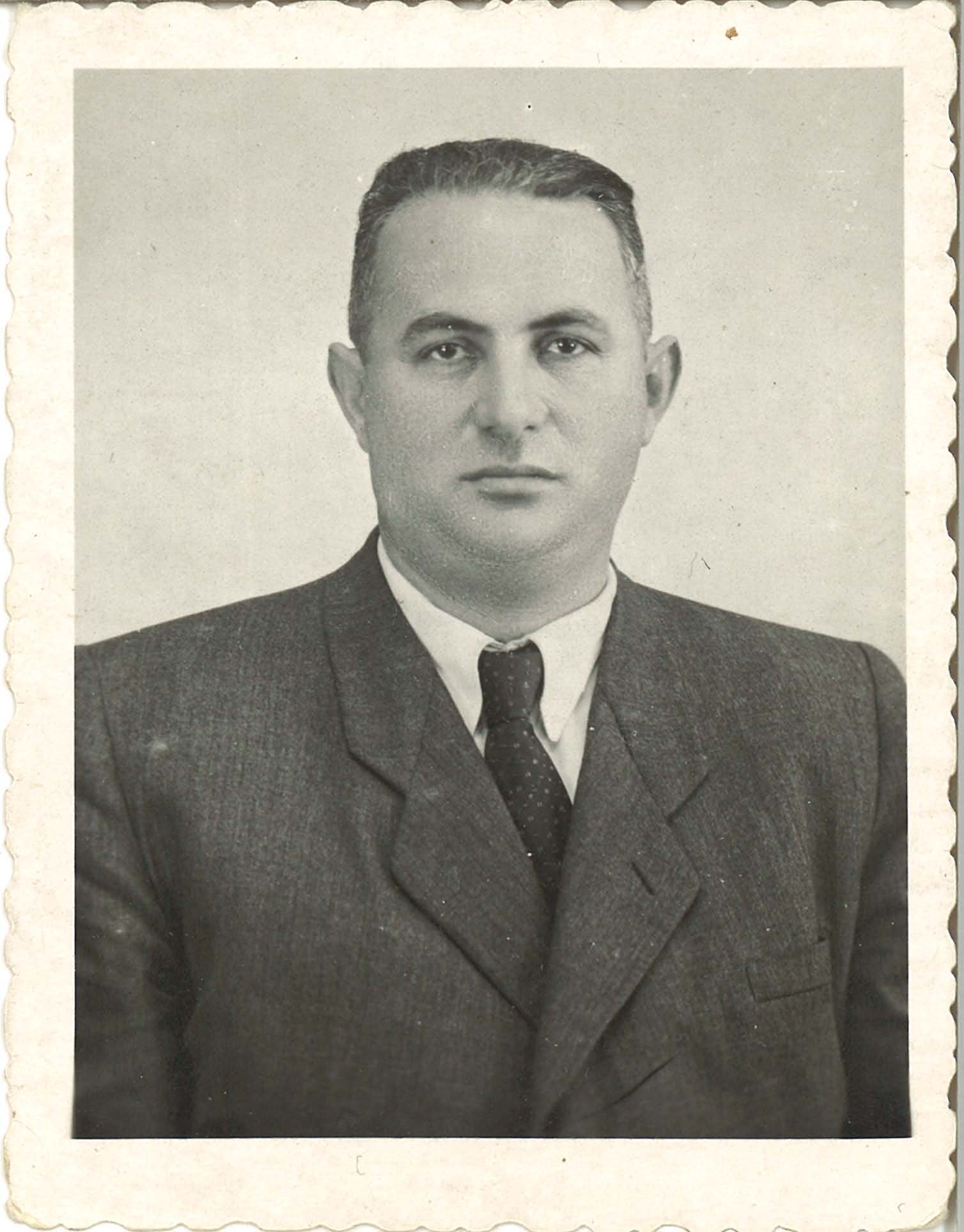

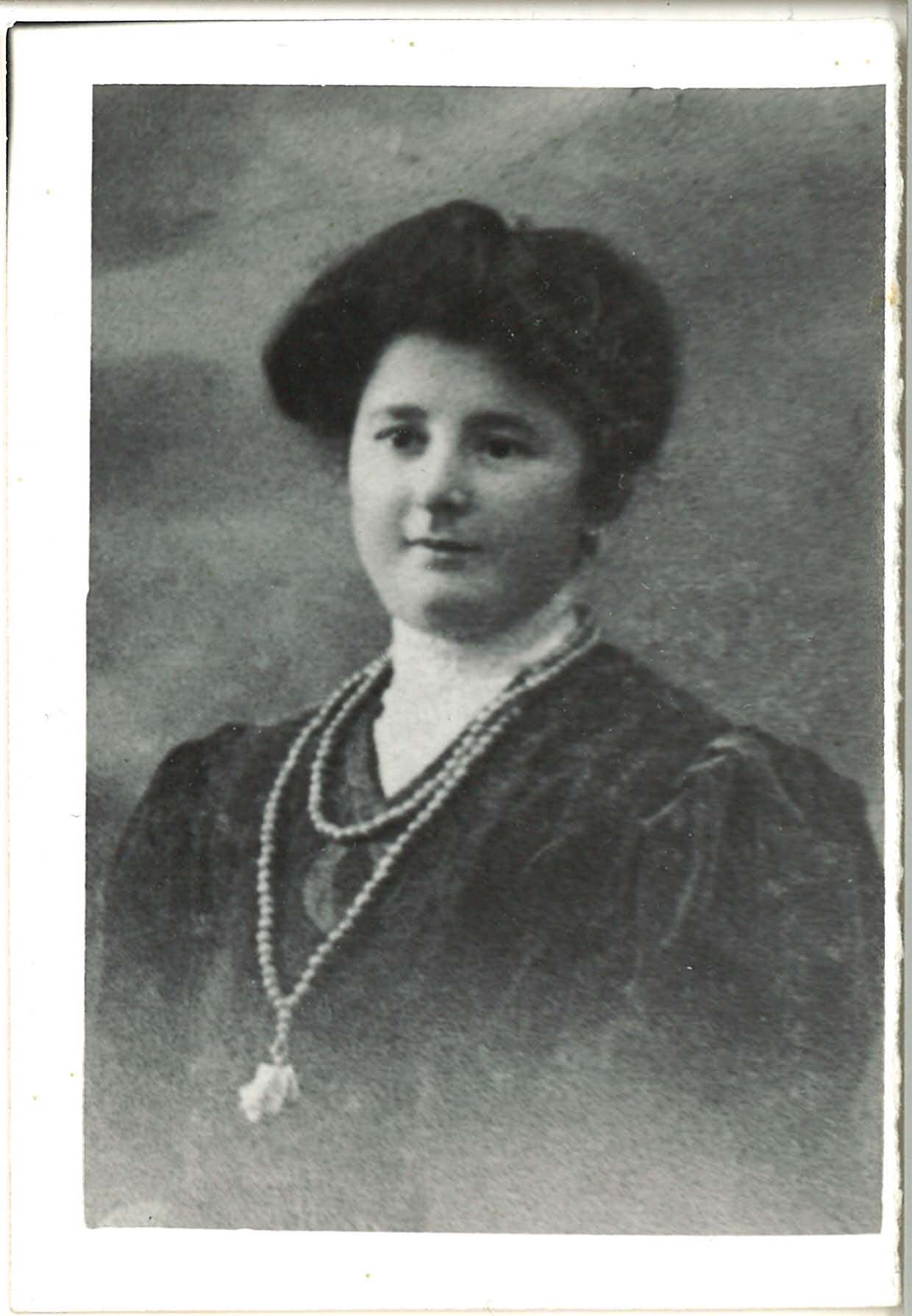

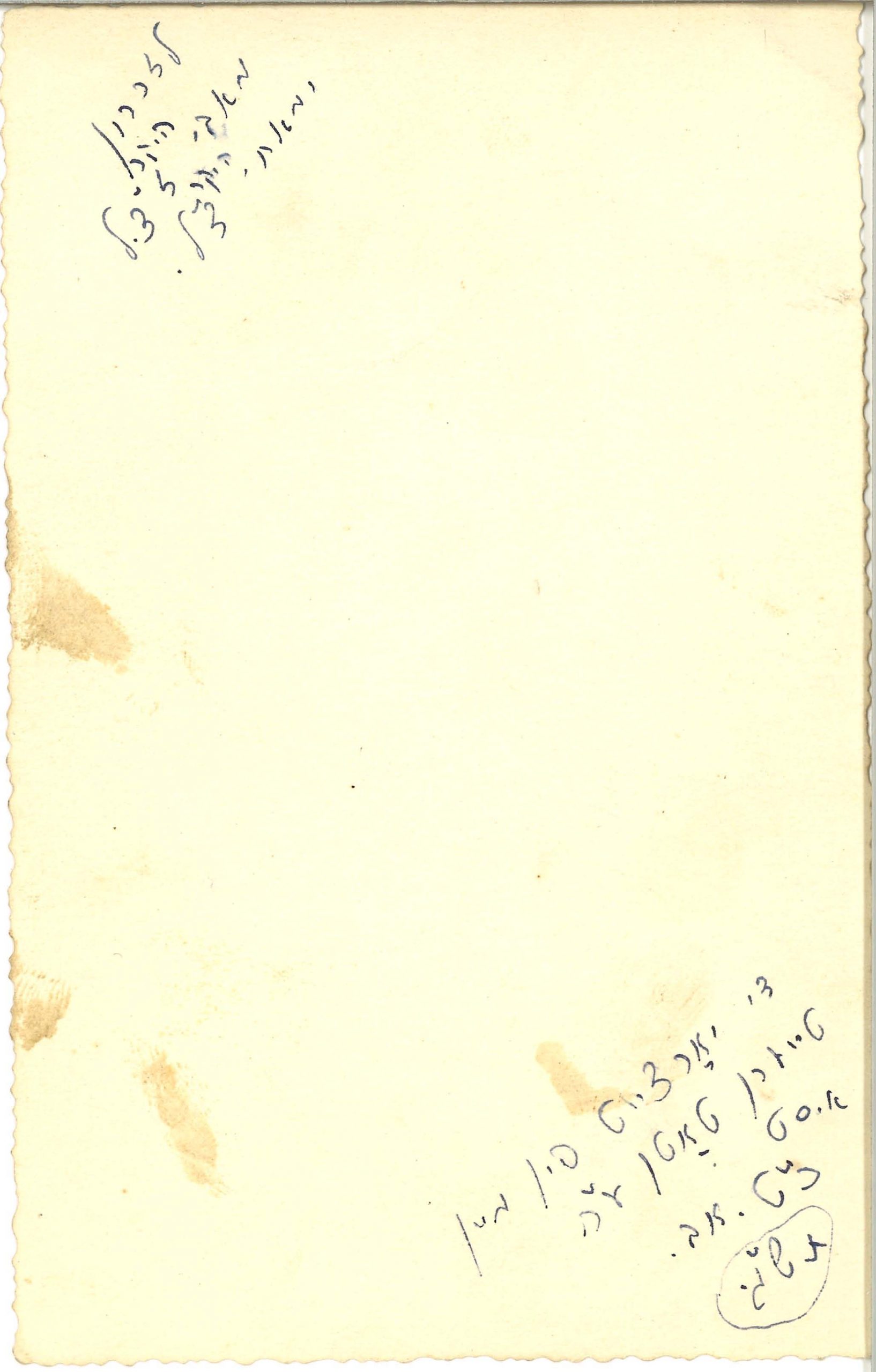

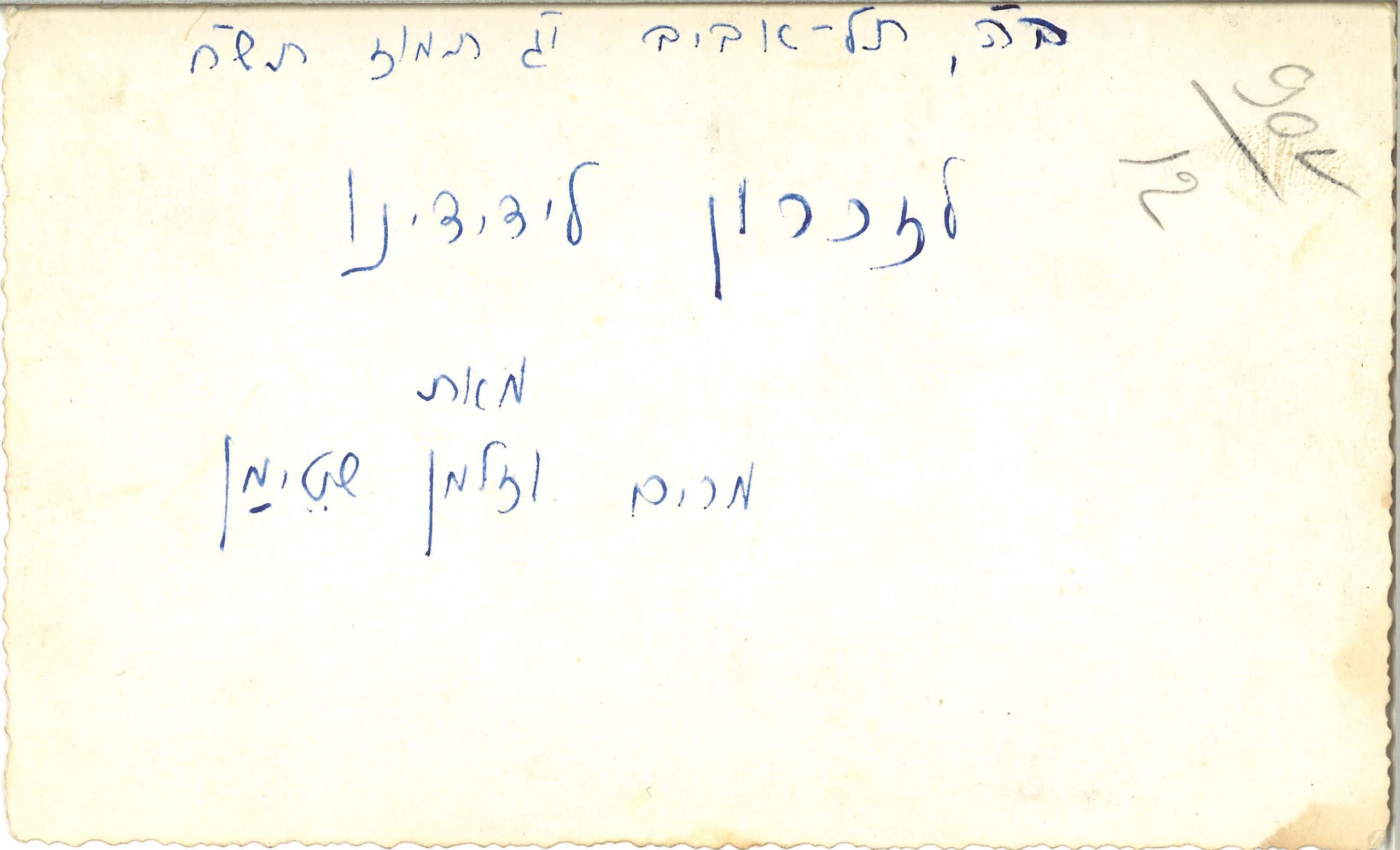

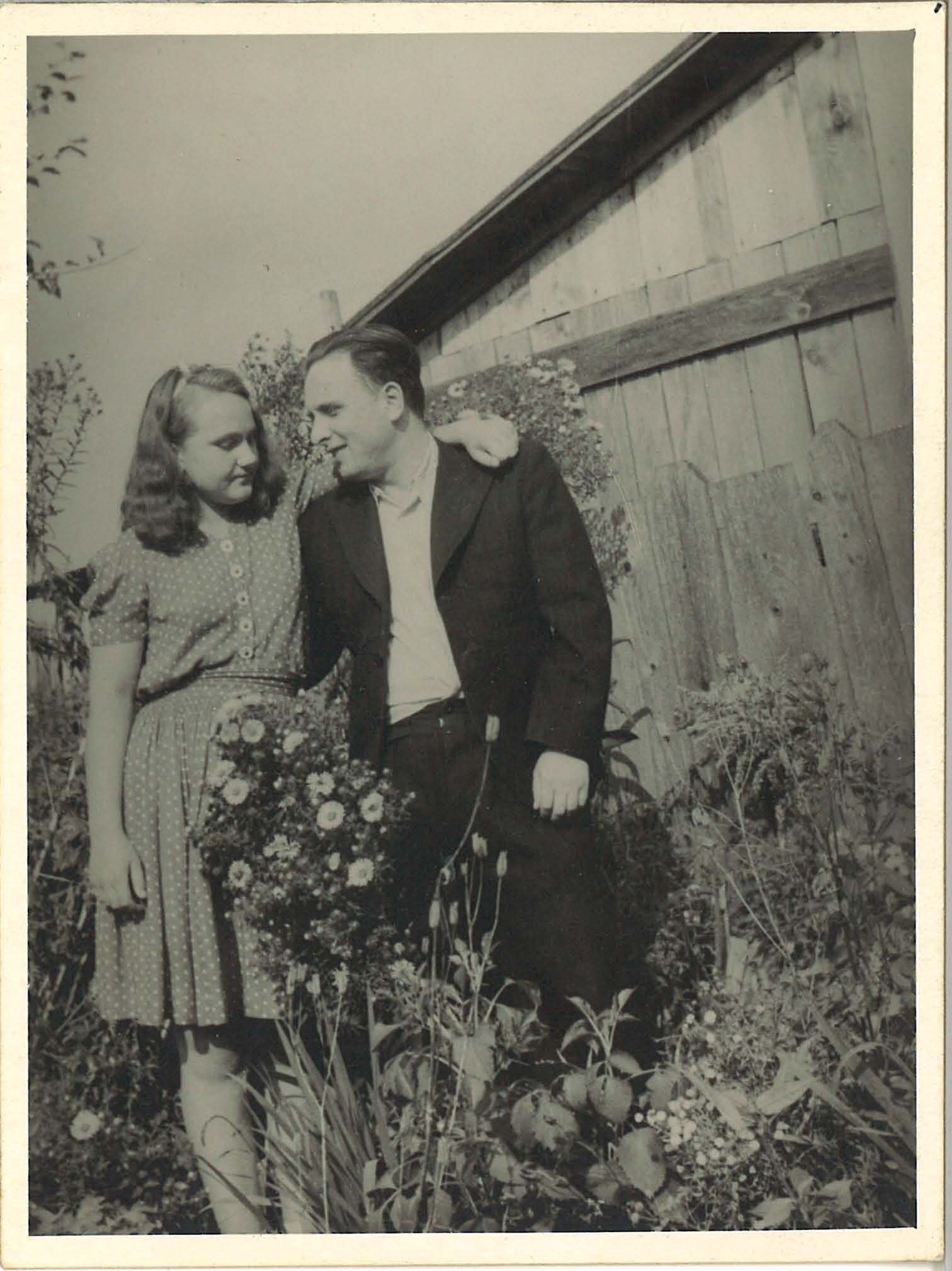

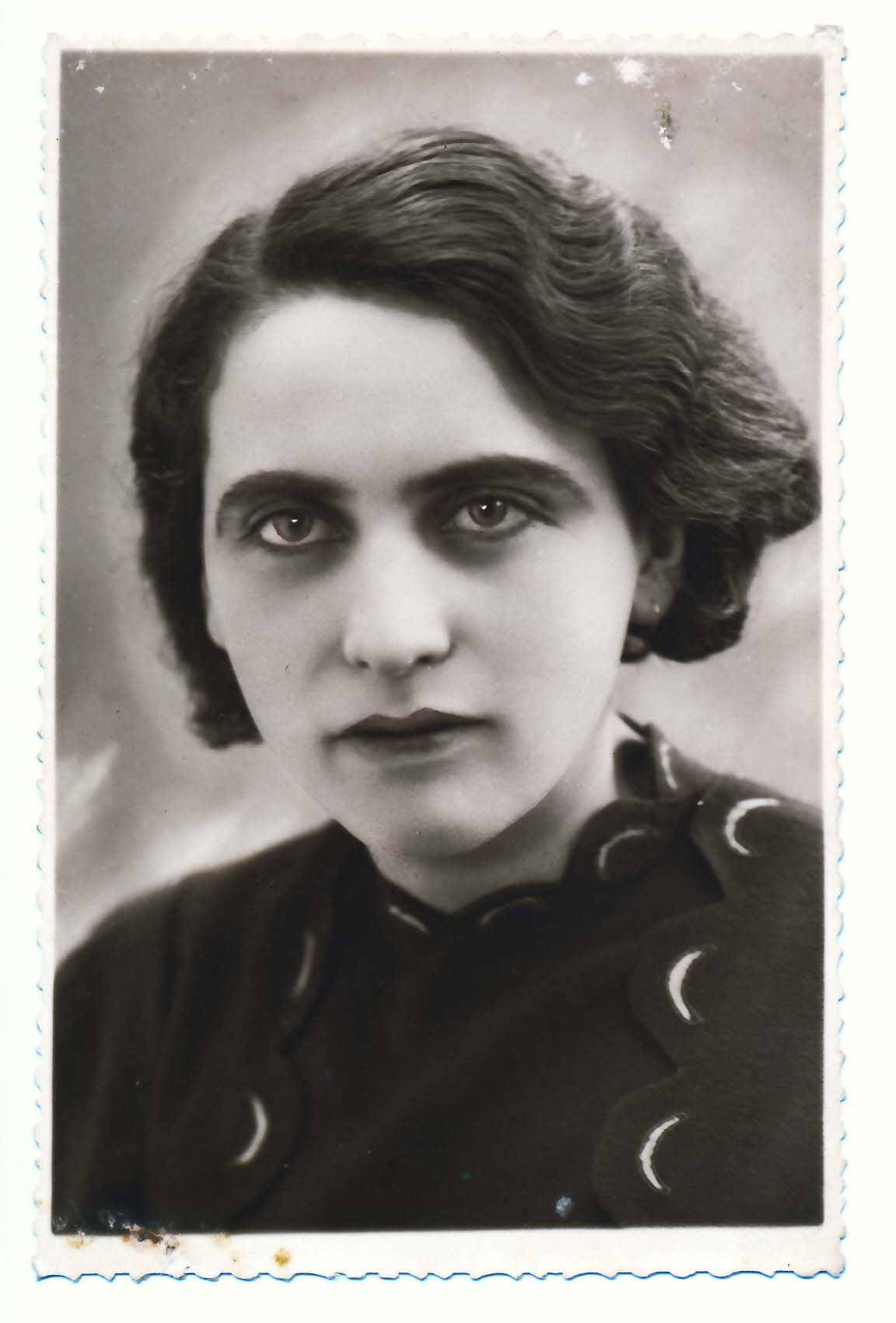

ARCHIVE PHOTOS

TIMELINE OF BARDEJOV JEWISH HISTORY

350 Cordova St., Pasadena, CA 91101 | 626.773.8808 | info@bardejov.org

Copyright © 2010 – 2026 Bardejov Jewish Preservation Committee. All rights reserved.